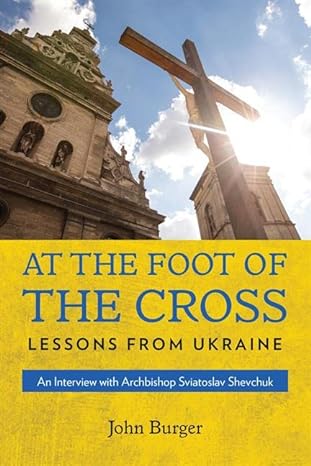

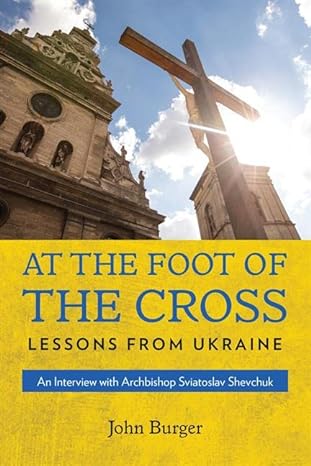

John Burger, At the Foot of the Cross: Lessons from Ukraine. An interview with Archbishop Sviatoslav Shevchuk. Huntington, Indiana: Our Sunday Visitor, 2023. ISBN 978-1-63966-027-8. Paperback $21.95 US.

The use of an interview with a prominent churchman in order to explore themes of contemporary religious life is a well-established practice. Italian journalist Vittorio Messori’s published interview with then-Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger (later Pope Benedict XVI) was translated from the German manuscript into Italian as Rapporto sulla Fede and into English as The Ratzinger Report, both in 1985. His written interview with Pope John Paul II was published as Varcare la Soglia della Speranza in 1994 and in English as Crossing the Threshold of Hope in the same year. Antoine Arjakovsky’s Conversations with Lubomyr Cardinal Husar: Towards a Post-Confessional Christianity was published in English translation from the French in 2007.

At the Foot of the Cross comprises four interviews by American Catholic journalist John Burger with Major Archbishop Sviatoslav Shevchuk. Following a foreword by Myroslav Marynovych, an introduction, and a chapter on Kyiv during the 2022 invasion, chapters 2 through 11 are based on in-person interviews conducted in August 2018 in Baltimore, in May 2019 in Ukraine, and in December 2019 in Philadelphia. Chapter 12 draws on a telephone interview with Archbishop Sviatoslav from June 2022.

The interviews deal with a variety of biographical as well as theological and political topics. As a child in Stryi, Sviatoslav Shevchuk had contact with the underground Ukrainian Greek-Catholic Church. Later, like many members of that network, he studied medicine (66, 142-3). This apparently contributed to his view of the church as a source of healing. In fact, the vision of the church as a “field hospital” was invoked early in his pontificate by Pope Francis – whom Sviatoslav had known when the future pope was still Cardinal Jorge Mario Bergoglio of Argentina. At that time a bishop for Ukrainians in Buenos Aires, the future head of the Ukrainian Greek-Catholic Church was also influenced by Cardinal Bergoglio’s emphasis on the duty of a bishop to serve rather than to be served. This view of episcopal service is particularly fitting in a world where the church is no longer backed by political power, and “the illusion of the Christian state” is a thing of the past. (108-110) Moreover, the down-to-earth Argentine Jesuit reminded the young prelate that reality is always more important than one’s ideas. (145)

At the same time, as a Byzantine-rite Catholic, Sviatoslav did not ignore Eastern theology. He wrote a dissertation on the 20th century Orthodox theologian Paul Evdokimov, who developed an Eastern Christian anthropology incorporating the insights of Swiss psychologist Carl Jung (94-6). This, he notes in the interview, allowed Sviatoslav to compare and contrast Latin and Byzantine views on human nature, sin, and grace. Sviatoslav’s understanding of the Eastern perspective also enriches his view of “synodality” – a much-discussed topic in today’s Roman Catholic Church. As he explains, synodality is perceived differently in the Greek-Catholic Church than it is in the Roman Church (116, 145-6).

There is, indeed, much that the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church can contribute to current discussions in the Catholic and broader Christian world. At a time when many Westerners have begun to doubt the value of their own European civilization, Ukrainians are fighting for the principles of that civilization. And Major Archbishop Sviatoslav has no doubt that European civilization is fundamentally Christian. “I believe,” he says, “that there is no Europe without Christian values and there is no European perspective without Christian roots.” Moreover, he believes that it is Ukraine’s special mission to help Europeans rediscover those values — which are, incidentally, the cornerstone of Catholic social teaching.

It is frequently argued, however, that America and Europe, even as they support Ukraine, project trends that corrode Christian values. As John Burger observes, Russia is holding itself out as a bulwark of Christianity and condemning Ukraine as an outpost of Western secularism. In reply, Archbishop Sviatoslav points out that measured by such indicators as Sunday church attendance, or the number of abortions, Russia is more “liberal” than many Western countries, and far more so than Ukraine (184). He does admit, however, that as a new and embattled democracy, Ukraine is like an open wound, prone to infection by various ideological “viruses” (184-5).

Can the Ukrainian state combat those corrosive influences? “I would not believe,” warns Sviatoslav, “that in today’s circumstances, a state, by its paternalistic protection of the Church, is able to foster Christian values.” (184) At the same time, the Church can provide “strong witness of Christian values inside a democratic, open society.” (185) For he believes that every human being is essentially religious, even if unconsciously. As the failure of the Soviet attempt to impose secularization showed, people naturally seek transcendence. Even as it shies away from organized religion, today’s youth is no exception. (186)

True, post-Soviet Ukrainian youth, reacting to Soviet collectivism and its suppression of the free individual, may find the Catholic church’s social teaching about community and the common good difficult to accept. (176-8) Many embrace “extreme individualism” (177). But the experience of the Maidan taught them the importance of community and solidarity, along with individual responsibility and private initiative. (177-8) Freedom, after all, is not just the absence of coercion. In fact, Sviatoslav believes that “we have to educate people to be free.” For inner freedom is a spiritual category, attainable only by truth and God’s grace. (179)

The Russian war against Ukraine is surely providing Ukrainian youth with a hard lesson in the value of freedom. But what can stop this war? Sviatoslav’s experience in the Soviet army has immunized him from illusions about the efficacy of diplomacy in dealing with Russia. (209) He believes that Vladimir Putin is using the invasion as a way to cope with Russia’s internal problems. Their messianistic, nationalistic pathology prompts many humiliated post-Soviet Russians to to try to “make Russia great again” by humiliating others. It is certainly not the fault of Ukraine, NATO, or the United States (210-211).

The interview also touches on the Ukrainian Catholic Church in the USA. Its experience has lessons for the home country. “Perhaps,” muses Sviatoslav, “we discover our weaknesses very often through the diaspora.” (172) Many of those who leave Ukraine exhibit a very low knowledge of their faith. (173) The church in America needs renewal. This also requires opening up to the surrounding culture and society.

“We are a Ukrainian Church, but we are a Church not only for Ukrainians.” (152) Being present in the American intellectual world is essential. Thus, the recent establishment of Eastern Christian studies at the Catholic University of America is a welcome development. (153) At the same time, it must be remembered that the diaspora affects developments in the homeland. (173)

Readers of this journal will be especially interested in the Major Archbishop’s views on the Patriarchate. Although he does not use the patriarchal title, he does not forbid it. In the Byzantine tradition, he notes, patriarchates “are not created but recognized” (162). The late Major Archbishop Lubomyr Husar emphasized the importance of the faithful building up the patriarchate by maturing as a church — by exercising their rights and learning to govern themselves. (162-4)

In response to John Burger’s question about a single patriarchate with the Orthodox, Sviatoslav refers to the 17th-century project of Metropolitans Peter Mohyla and Josyf Veliamyn Rutsky for a joint Orthodox-Uniate patriarchate of Kyiv. (166-7) But before communion can be achieved, the Orthodox must unite among themselves, and find their place in world Orthodoxy. (168-9)

Sviatoslav’s vision of Catholic-Orthodox ecumenism is not, however, centered on structural unification, uniformity, and jurisdiction, but on communion (146-7, 151). And he is well aware that history has made the Orthodox distrustful of Catholic ecumenical initiatives. “We have to witness to the Orthodox that communion with the Holy Father doesn’t mean a submission or loss of identity,” he stresses. “The fullness of Orthodoxy will flourish inside communion with the successor of Peter…. The successor of Peter, with his collaborators in the Roman Curia, [has] to show through the relations toward us how [he] would like to treat the Orthodox, when one day they will restore communion with the successor of Peter.” (150) In the meantime, the laity have taken the lead: “… I have to say that at the grassroots level, simple believers are further ahead in the ecumenical movement than the monastic communities or clergy.” (168)

In his introduction, John Burger recalls that when Fr. Volodymyr Malchyn, then a member of Major Archbishop Sviatoslav’s staff, mentioned the idea of a biography of the head of the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church, Burger warned him that he should not expect to see a draft of the book before publication, because a public-relations effort on behalf of the Church or its head would lack credibility (17-18). Although the final product was a book-length interview rather than a biography, the journalist evidently adhered to his principles. He asked difficult, probing questions, which remained in the text even when not fully answered. Thus, as Myroslav Marynovych notes in his foreword, the interviewee “bypassed the question about what concerns about the laity in the Church he sees.” Marynovych concludes that perhaps it was better, after all, not to mention the weaknesses of the laity (p. 12, referring to a question and response on pp. 151-2). The point, however, is that Burger did not delete the unanswered question. Similarly, when the interviewer asks Sviatoslav how the Church can teach the Gospel to people who have no interest in religion, the latter admits that he has no simple answer, because the problem is complex (179). In other words, this book is not mere propaganda.

For the church, after all, has no need for propaganda (except in the earlier Latin sense of propagare fidem). Unlike Marxism, Christianity does not pretend to have the answer to every human question. Rather, the church seeks to lead people toward God and the mystery of his truth. This book tells us a lot about how she is doing that.

Andrew Sorokowski

1 Andrew Sorokowski is retired from the U.S. Department of Justice, where he served as a researcher in the Environment and Natural Resources Division. He is president of the Ukrainian Patriarchal Society in the USA.