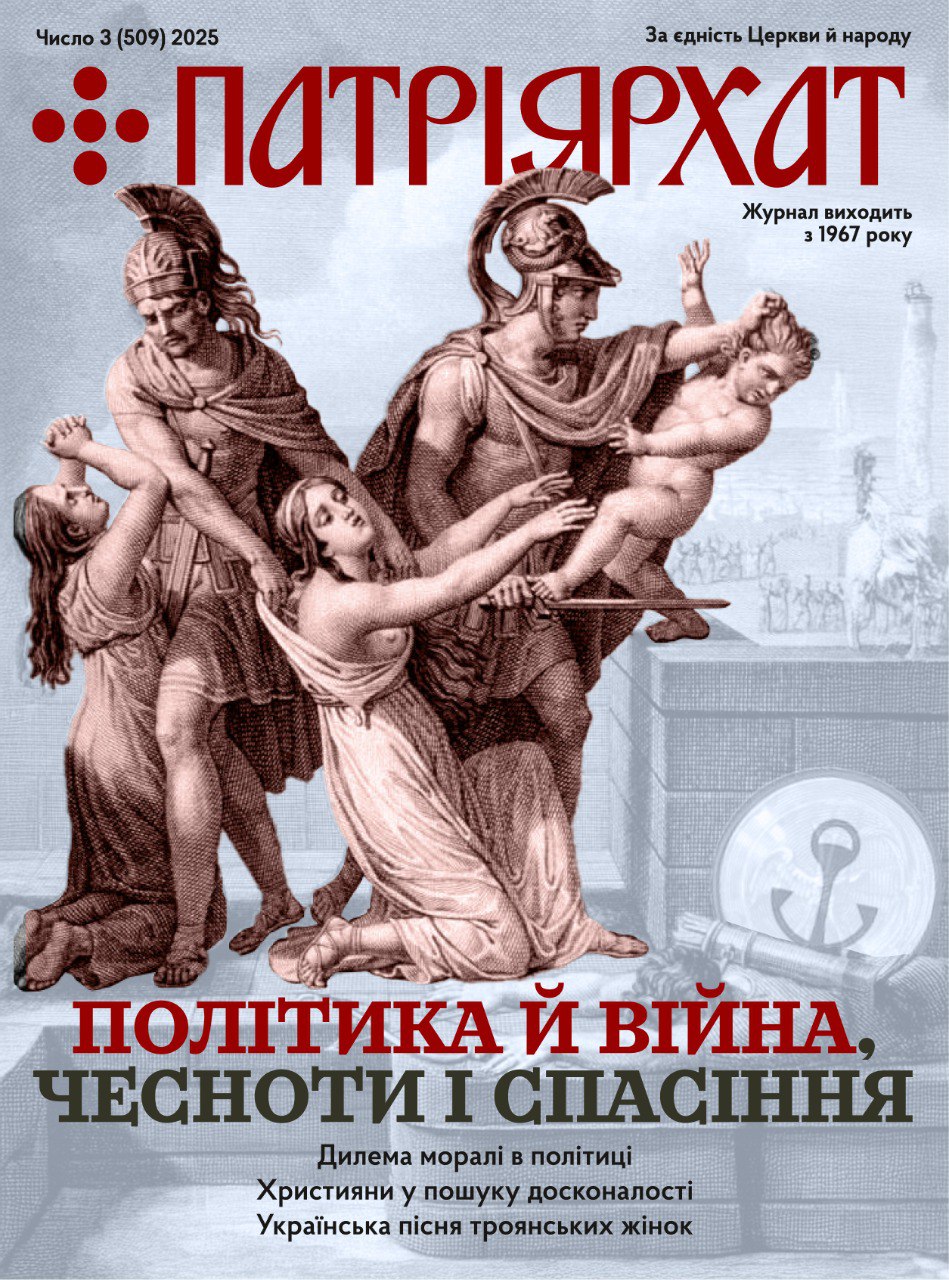

Ukrainian vs. Roman

Press reports of protests by Ukrainian Catholics demanding recognition of the autonomy of their Church have failed generally to convey the significance of the issues in question. The Orthodox heritage of Eastern Catholicism and the prophetic vision of the Second Vatican Council are both confronted by Roman bureaucratic intransigence, a situation similar to those which precipitated earlier schisms. If a break should occur, or if the Ukrainian Church should be obligated to submit to Roman demands, the consequences would be tragic not only for the Ukrainian Church and the other Eastern Catholic Churches, but also for Catholicism’s relations with Eastern Orthodoxy and for the Roman Church’s own prospects for structural renewal.

The Second Vatican Council, responding in particular to the interventions of His Beatitude Joseph VII Slipyj, Major-Archbishop of the Ukrainian Catholic Church and His Beatitude Maximos IV Saigh, Patriarch of the Melkite Greek Catholic Church, sought to affirm the apostolicity, integrity, and «equal dignity» of the several Oriental Churches which are in communion with the Church of Rome. The Council Fathers not only honored the «ecclesiastical and spiritual heritage» of the Eastern Catholic Churches «with merited esteem and rightful praise,» but went so far as to declare «solemnly», with a degree of authority invoked on only one other occasion, «that the Churches of the East, as much as those of the West, fully enjoy the right, and are in duty bound, to rule themselves. Each should do so according to its proper and individual procedures, inasmuch as practices sanctioned by a noble antiquity harmonize better with the customs of the faithful and are seen as more likely to foster the good of souls».(Quoted from the Decree on Eastern Catholic Churches). Not only did the Fathers eulogies the Eastern heritage and restate in the strongest possible language the Eastern Churches’ obligation to rule themselves, but they recommended, for both sociological and spiritual reasons, that the Eastern Churches adhere to the structural and governmental styles proper to their tradition.

In respect to patriarchal Churches, the Council also reminded Catholicism that the «Patriarchs with their synods constitute the superior authority for all affairs of the patriarchate», and decreed that the «rights and privileges» of the Oriental patriarchates «should be reestablished in accord with the ancient traditions of each Church and the decrees of the ecumenical Synods». Lest there be any doubt, the Fathers specified that the «rights and privileges in question are those which flourished when East and West were in union», that is, prior to the Great Schism of 1054 and the subsequent administrative centralization of the Roman Church.

Finally, to make the point that the non-patriarchal Eastern Churches, such as the Ukrainian Church, are not merely ornamental variations of Latin Catholicism, the Council stated that «what has been said of Patriarchs applies as well, under the norm of law, to major archbishops, who preside over the whole or some individual. Church or rite*. Indeed, «inasmuch as the patriarchal office is a traditional form of government in the Eastern Church, this Sacred and Ecumenical

Council earnestly desires that where needed, new patriarchates should be erected.» This might be done however, only with the approval of an Ecumenical Council or of the Roman Pontiff.

Although the Oriental bishops generally found the juridical language and Curial perspective of the Degree on the Eastern Catholic Churches less than adequate, and although the Council’s statements of principle were hedged about with references to «the inalienable right of the Roman Pontiff» — that is, the Pope himself, not the domestic administrative machinery of the Western Church — «to intervene in individual cases», they voted for the Decree, hoping that the Conciliar document would in fact lead to the realization of the «equal dignity» of the Oriental Catholic Churches.

In autumn of 1969, Major-Archbishop Joseph VII convened an Archiepiscopal Synod of the Ukrainian Catholic hierarchy to advance the organization of a Ukrainian patriarchate. Suffering severe persecution in their homeland and the effect of dispersal elsewhere, the Ukrainians felt that the symbol of a patriarchate would serve to maintain the cohesion and identity of their Church. Yet the Secretary of the Sacred Oriental Congregation, Maximilian Cardinal de Furstenberg, attempted to nullify the synodal status of the 1969 meeting, and sometime later the Major-Archbishop was informed by the Pope that the effort to erect a Ukrainian Patriarchate was inopportune. Accepting this decision, the Major-Archbishop was for the moment satisfied to continue pressing for the development of an operative synodal government for the Ukrainian Church.

The next attempt to convene a Ukrainian Synod was frustrated when the Curia prevented the Major-Archbishop from attending a planned convocation of the Ukrainian hierarchy in Canada. Finally, another Ukrainian Synod was called in October, 1971, at a time representatives of the whole Catholic episcopacy came to Rome to meet as an advisory Synod. Before the Ukrainian bishops could assemble, they received from the Secretary of State, Jean Cardinal Villot, a letter expressing Vatican opposition to the convocation of any canonical synod of Ukrainian bishops. The Ukrainians met anyway, and asked the Pope’s blessing upon their proceedings. That blessing was not forthcoming, and the Pope declined to acknowledge the synodal character of their meeting. Nonetheless, the Ukrainian hierarchs continued deliberating. Before adjourning, they elected a Permanent Synod of five bishops to oversee the affairs of the Ukrainian Church, and directed that Synod to draft an Archiepiscopal Constitution.

In early 1972, the Permanent Synod circulated its draft constitution among the Ukrainian bishops. But then, in September 1972, each Ukrainian bishop received a letter from the office of the Secretary of State declaring that the «Holy See cannot accept such a ‘Constitution’ as canonically workable.» The Vatican letter was issued at the direction of Cardinal Villot «by mandate received from our Holy Father» and was dispatched to individual Ukrainian bishops through Roman administrative channels. Evidently, no copy was addressed to the Major-Archbishop himself.

The Vatican letter made four points. First, it protested that both the drafting and circulation of the Ukrainian constitutional text had «occurred without the knowledge of the Holy See». Secondly, it claimed that «no juridical title apt to legitimate such a ‘Constitution’ can be found: particularly because the Ukrainian Church is not constituted as a patriarchate, and, as a whole, has no intermediate jurisdictional structure between the episcopal and the papal authority.» Third, it asserted that the draft constitution’s reference to the Ukrainian Church as ‘«autonomous’ is neither juridically perspicuous, nor does it conform to the customs of the other Eastern Catholic Churches.» Finally, the letter concluded by inviting the Ukrainian bishops, as individuals but not as a corporate synod, to offer their advice and insights to the Roman commission engaged in systematizing a code of canon law for the Eastern Catholic Churches.

The contrast between the Secretariat of State’s letter and the tenor of the Vatican Council’s enunciation of principles illustrates the basic conceptual difficulty complicating relationships between the Latin and the Oriental Catholic Churches. Specifically, the Roman and the Ukrainian Churches employ different understandings of ecclesiological process. The Vatican letter assumes that both constitutional development within any Catholic Church, Oriental as well as Occidental, and also the internal procedures contributing to such evolution must first be juridically legitimated by prior authorization from the Roman See. In substance, it articulates the Curial viewpoint that Rome possesses exclusive authority to initiate structural reform with the Churches of the East.

The Oriental Churches, especially those which adhere most faithfully to Orthodox tradition, understand constitutional development to be an indigenous organic process, guided by the Holy See in response to concrete circumstances and circumscribed only by the need to preserve doctrinal orthodoxy and the bond of loving communion. According to this point of view, the organic growth of each Eastern Church is fundamentally rooted in Her own culture, custom, and heritage. Through the episcopacy, the heritage of each Eastern Church extends back to the college of the Apostles, whence the Apostolic authority of each Church’s episcopacy is derived. Periodically, as her tradition encounters new situations, each Church, in fulfillment of her own historical and prophetic vocation, is summoned by the Holy Spirit and by the needs of men to adapt her customs, so that her proclamation of the Gospel may continue to be clearly heard. The communion of the several Churches of the East and the West, a communion personified and made concrete through their common Eucharistic fellowship with the Pope of Rome, serves to guarantee mutual orthodoxy and mutual fidelity to the one Gospel. Communion also pluralistic variety of the Church, and of the Kingdom announced by the Gospel. But communion does not give any Church license to interfere arbitrarily in the domestic disciplinary, structural, liturgical or canonical affairs of another orthodox Catholic Church.

(To be cont.)