To commemorate the 60th anniversary of our Patriarch’s priesthood ordination,

we are reprinting an article which was published in the October 30 1971

issue of the American magazine «Saturday Review».

The author of the article, Norman Cousins, actively participated in the efforts to release

Metropolitan Josyf Slipyj from his imprisonment.

Our readers should acquaint themselves with this article for it presents an accurate

and factual account of His Beatitude’s road to freedom.

The editor

by NORMAN COUSINS

In 1963, a new spirit of hopefulness was abroad in the world. The upturn was largely the result of a strange and magnificent interaction among three men: President John F. Kennedy, Pope John XXIII, and Prime Minister Nikita Khrushchev. Ideologically and personally, they were one of history’s most implausible triumvirates: an American President, a Pope, a Communist. What brought them together was the vulnerability of civilization to modern destructive power. The particular event that gave blistering reality to their common concern was the Cuban crisis of October 1962.

The crisis over Cuba was bridged but the terror it produced created a new sense of resolution and dedication.

At American University on June 10, 1963, President Kennedy proposed an end to the Cold War. The proposal produced an affirmative response from Prime Minister Khrushchev. Pope John used the full weight of the Papacy to speak about the need for world peace under law. His encyclical Pacem in Terris was perhaps his single most important document. It called for a new spirit of world cooperation in building an enduring world order.

The three men had a profound respect for one another; to the United States to attract support for his university.

Pro Deo had, from its start, been interreligious and international, a fact he attributed in large part to the influence of Pope John XXIII and Cardinal Montini, who later became Pope Paul VI. Father Morlion spoke of his hopes for die development of Pro Deo University as a training center for world citizenship, bridging gaps not just between East and West but within the West itself; gaps, too, between theologian and scientist, philosopher and activist.

Father Morlion was also interested in advancing the ideas of Pope John. At that time, the profound changes inside the Catholic Church that were to be associated with Pope John were not yet in public view.

«You must believe me,» Father Morlion said, «when I tell you that dramatic ideas for change inside the Church are now in the making. All the world will come to acclaim and love this gentle man. Pope John. He sees and feels beyond Catholicism. He has a deep-felt respect for people of all faiths. He wants to help save the peace.»

Father Morlion said Pope John was encouraged by the growth of anti-war forces inside the Soviet Union. These long-awaited opening-up trends inside Russia were profoundly significant, he said, and ought to be explored and to widened, if possible.

All understood the extent to which their combined role was historically necessary, however diverse or contradictory their backgrounds. For a brief period: their candle burned brightly. Then very quickly, the trio was lost to history. President Kennedy was assassinated, Pope John died of cancer, and Nikita Khrushchev was replaced in office.

The recent death of Khrushchev has stimulated recollections concerning the relationship among these three men. The account I give here—most of which concerns Khrushchev—is hardly more than an asterisk to history, but it does bear upon the remarkable exchanges among the trio. Through a strange combination of circumstances, I found myself an emissary for Pope John to the Kremlin. An off-shoot of this mission involved President Kennedy. I have not written about this episode previously because much of it was in the nature of confidential information involving the Vatican and the Kremlin. Recently, however, reports originating in Rome have quoted Catholic sources on the early portions of this narrative. Under the circumstances, there no longer appears to be reason for withholding these recollections.

The story begins in New York in March 1962, when Father Felix P. Morlion, President of Pro Deo University in Rome, visited the offices of Saturday Review. He had come in the fall of 1962, a conference between Americans and Russians was held in Andover, Massachusetts. It was the third in a series of meetings that had begun at Dartmouth College several years earlier. The purpose of the conferences was to explore, on the private and unofficial level, problems facing both nations. The hope was that informal understandings could be reached that might be of some use to government leaders in both countries.

We began our meeting the evening of October 21, minutes before President Kennedy announced he was ordering American naval vessels to intercept Soviet shipping to Cuba. He said that the United States had learned of missile sites being constructed in Cuba under Russian direction. He said he recognized the seriousness of his action but that the United States was confronted with a threat to its security it could not accept.

Both delegations at Andover knew that nuclear war might be imminent. The United States and the Soviet Union were on a collision course.

At the height of the Cuban crisis, Father Morlion came to Andover. He thought Papal intervention in the Cuban crisis was essential and possible, enabling each side to react to an outside proposal, whereas the same proposal made directly by either party might be rejected automatically by the other without regard to merit. With the encouragement of those members of both delegations whom he had taken into his confidence, Morlion telephoned the Vatican. A few hours later he gave us word that Pope John was intensely apprehensive about the Cuban crisis and wanted to help avert a ghastly confrontation. The Pope was eager to play a useful role if this was agreeable to both parties. Would a proposal be acceptable that called for a withdrawal of both military shipping and the blockade?

I telephoned the White House and spoke to Ted Sorensen, who conferred with the President. He said the President welcomed the offer of Pope John’s intervention and, indeed, welcomed any initiative that would prevent an escalation of the Cuban crisis. But the President could not encourage Pope John to believe that his proposal was directed to the central issue. That issue was not so much the shipping but the presence of Russian missiles on Cuban soil. Those missiles had to be removed—and soon— if the consequences of the crisis were to be averted.

I relayed the information to Father Morlion, who telephoned the Vatican. Father Morlion also consulted with the leaders of the Soviet delegation at Andover, one of whom telephoned Moscow and reported that the Pope’s proposal calling for withdrawal of both the military shipping and the blockade was completely acceptable to Premier Khrushchev.

The next day Pope John issued his call for moral responsibility in the Cuban crisis. In line with President Kennedy’s reservations, he made no specific reference to the military shipments or the blockade. Instead, he directed himself to the clear obligation of the political leaders to avoid taking those steps that could lead to a human holocaust. He said that not just the Americans and the Russians but all the world’s peoples were involved, and that their fate could not be disregarded. He said that history would praise any statesman who put the cause of mankind above national considerations.

The Pope’s appeal made headlines throughout the world, including the Soviet Union.

At week’s end, Premier Khrushchev announced he was removing the missiles from Cuba and had written a long letter to President Kennedy. He said he hoped that the lessons learned during this crisis could be profitably turned to the promotion of peace.

It was against this background of the Pope’s message on Cuba that Father Morlion informally explored with some of the Soviet delegates the possibility of direct communication between Rome and Moscow in the cause of a workable peace. He said he knew how implausible this sounded given the historical incompatibility between these two groupings, but humankind was now faced with overriding needs. He told the Russians he had reason to believe that I would be acceptable to the Vatican for the purpose of undertaking preliminary contacts between Rome and Moscow, and he asked if I would be equally acceptable to the Russians.

The Soviet delegates said they would make inquiries on all these points after they returned to Moscow, and would reply by letter or cable.

Shortly after I returned to New York, I received a telephone call from Ambassador Anatoly F. Dobrynin in Washington. He said the project proposed by Father Morlion at Andover had been approved and that December 14 was suggested as a possible date for a visit by me to Premier Khrushchev in Moscow on behalf of the Vatican.

Under U.S. law American citizens are forbidden to hold discussions with heads of governments on matters that could have a bearing on the policies of those countries toward the United States. Although the United States was not directly involved in my private mission, I thought it best to inform Washington. I sought the advice of Pierre Salinger, the President’s press secretary. Two days later he telephoned me in New York to say he had spoken to the President and that there were no objections to the trip. Salinger said that Ralph Dungan had been assigned by the President to follow the project and keep him informed. The President also felt he ought to speak to me just before my departure.

Several days later I was called to the White House. 1 went through the front gate at the White House, where my name was checked off the guard’s list. Then I was escorted into the Cabinet Room on the ground floor; it looked out on a garden enclave and adjoined the portico connecting the living quarters of the White House with the Executive offices. Beyond the enclave was the White House lawn, which seemed far less manicured and level than it appeared from the street. I observed several well-sheltered nooks, one of which was modestly equipped with playground facilities. A half-dozen youngsters, ages four to eight, were romping around, chaperoned by two well-dressed young ladies, one of whom looked like the President’s sister. A slender young man joined the group and stooped to chat with the children. When he straightened and turned around, I could see it was the President. He spent perhaps five minutes with the children and then entered the Executive offices.

The President greeted me in the Cabinet Room. He was superbly tanned and radiated good health and spirits. He took me into his office and said he had been fully briefed by Ralph Dungan. One of the principal hopes for world peace, President Kennedy said, was that the leaders of the Soviet Union would continue their break away from Stalinist habits, suspicions, goals. There was no alternative to peace among the great nations, especially between the Soviet Union and the United States. He said he believed in creating genuinely amicable relations with the Soviet Union. He hoped we had been through the worst of it with Cuba.

The President said the Russians had miscalculated badly in Cuba. They had assumed we intended to invade.

«We never had any intention of invading Cuba,» the President added. «Certainly there were those who advocated an invasion, but I decided against it for one simple reason: It would have killed too many Cubans. This was why we didn’t commit our forces in the Bay of Pigs episode. Anyway, the Russians made a serious miscalculation of our intentions.»

However, he said, the important thing now was to get on with the business of reducing tensions. One immediate positive measure that might be taken was an agreement to outlaw nuclear testing. But, he added, Russian leaders seemed overly suspicious and held back in agreeing to even the minimal inspection that would have to be part of any such comprehensive test ban.

The President got up from his rocking chair and walked over to the window. He was reflective. After a moment he turned and said, «You’ll probably be talking with Mr. Khrushchev about improving the religious situation inside the Soviet Union, and I don’t know if the matter of American-Soviet relationships will come up. But if it does, he will probably say something about his desire to reduce tensions but will make it appear there’s no reciprocal interest by the United States. It is important that he be corrected on this score. I’m not sure Khrushchev knows this, but I don’t think there’s any man in American politics who’s more eager than I am to put Cold War animosities behind us and get down to the hard business of building friendly relations.»

Before I left I was given a letter that asked me to convey the President’s Christmas greetings to Pope John and his good wishes for the Pope’s full recovery from his illness, the seriousness of which was not known at that time.

I left for Rome on December 1, 1962. It was a comparatively slow flight, with stops in the Azores and Spain. I had a chance to think quietly and consecutively. Could anything be more improbable than attempting the job of messenger boy between the Vatican and the Kremlin? One point that troubled me had to do with Father Morlion’s belief that the time might now be propitious for seeking an amelioration of the religious situation inside the Soviet Union. Did this mean amelioration for Catholics only, or was the attempt to be in behalf of all religions?

When I arrived in Rome late in the afternoon, Father Morlion, rotund and beaming, was at the gate to the terminal. On the drive to the hotel, we discussed the plans for my meeting with Vatican officials, beginning that evening with a visit to the home of Monsignor Igino Cardinale, Chief of Protocol in the Vatican Department of State. Then, on the next day, there would be separate meetings with Archbishop Angelo Dell’Acqua, Deputy Secretary of State, and Cardinal Augustin Bea, president of the secretariat in charge of relations of the Ecumenical Council with non-Catholics.

After dinner at the hotel that evening, we called on Monsignor Cardinale. He spoke English with a distinct American accent—the result, I learned, of his upbringing in Brooklyn, New York. He had come to Rome in 1938, where he worked as a chaplain in various parishes from 1941 to 1946, when he was appointed Secretary to the Apostolic Delegation to Egypt, Palestine, Transjordan, Arabia, and Cyprus. He was appointed Chief of Protocol under Pope John in 1961. He had also written with distinction in the field of Papal policy on world affairs, his main work, Le Saint-Siege et la Diplomatic, being the only treatise of its kind on Papal diplomacy available in modern times.

We plunged into the matter of the mission to Moscow. He said the time was most auspicious for such an undertaking and that every effort should be made to take advantage of whatever constructive new openings might exist in the Soviet Union. He was apprehensive about the increase of China’s influence inside the Communist world, and believed the defeat of Khrushchev’s co-existence policies could have serious implications. He thought it might be useful to seek some level of representation by the Church inside the Soviet Union—on the assumption, of course, that there would be a genuine improvement in the religious situation inside the Soviet Union.

Monsignor Cardinale stressed the need for total secrecy of the mission. He explained that if the story broke, it would probably be necessary for all sides to repudiate it.

In response to my question about the Pope’s health, the Monsignor confided that the Holy Father’s illness was not a temporary indisposition, as had been reported in some newspapers, but a painful and malignant disease. The Pope showed physical evidence of the suffering but astounded the men close to him with his determination to carry on the main part of his work.

The Monsignor then brought me to the office of his superior, Archbishop Dell’Acqua. The Archbishop began the meeting by saying he understood I had come with a Christmas greeting for the Holy Father from President Kennedy. He added that, in view of the Pope’s condition, it would not be possible to see him at this time but that he hoped the Pope would be well enough to see me upon my return from Moscow. He said it was of the utmost importance for the Church to take into account the many new changes inside the Soviet Union under Khrushchev. If these changes meant that the danger of a nuclear war was lessened, then it was natural and right that these changes be recognized and welcomed. And if, furthermore, the changes meant there was any prospect for an improvement of religious conditions inside the Soviet Union, that chance couldn’t be ignored. He hoped I might be able to make Known to Premier Khrushchev the great value placed by the Holy Father on world peace. Also, the Pope was mindful of Premier Khrushchev’s statesmanlike action in withdrawing the missiles from Cuba.

«As the Pope said in his message during the Cuban crisis, he will go out of his way to praise any man in government who is able and willing to help spare mankind the holocaust of war. When you see Khrushchev, you must be sure to mention this. It is important to know, too, whether the Soviet Union would welcome further intervention by the Holy Father in matters affecting the peace.»

The next morning I went to the office of Cardinal Bea. His intellectual vigor quickly belied his eighty-one years. Like Archbishop Dell’Acqua, he believed that the smallest possibility for bettering the conditions of the Soviet people should be explored.

The central question, of course, was whether such explorations would be welcomed on the other end. Was there anything specific I might ask for in Moscow that would indicate a positive response? For many years, he said, members of the religious community had been imprisoned inside the Soviet Union. It would be a most favorable augury if some of them could be released.

Was there any particular person he had in mind? I asked.

«Yes,» Cardinal Bea said, «Archbishop Josyf Slipyi of the Ukraine, who has been imprisoned for eighteen years. The Holy Father would like the Archbishop to live out his few years in peace at some seminary. There is no intention to exploit the Archbishop’s release for propaganda purposes.»

«Is there anything else I might ask for?»

The Cardinal agreed with Monsignor Cardinale and Archbishop Dell’Acqua that this might be a good time to press for improvement of religious conditions within the Soviet Union. It was difficult to obtain Bibles; religious education was proscribed; seminaries were being closed. Perhaps these matters might be explored.

«Premier Khrushchev probably thinks we want to restore the Church to what it was in pre-Revolutionary Russia,» the Cardinal said. «Not true. There were many abuses by the Church at that time. In many respects, it was a terrible situation. This is not our idea of the proper role of the Church.»

It seemed to me that this was a good time to express my apprehensions. And so I asked whether the representations were to be made in behalf of Catholicism or all religious beliefs. There had been many disquieting reports of anti-Semitism in the Soviet Union. Wouldn’t it be strange to discuss the conditions of religious worship in the Soviet Union without referring to this most striking example of discrimination?

Cardinal Bea was emphatic in saying he hoped I would express Pope John’s deep interest in the condition of all religions in the Soviet Union. He also urged me to make known to Mr. Khrushchev the Holy Father’s profound concern over the treatment of Jews there.

Would it also be agreeable to take up with Mr. Khrushchev the right to publish not only the New Testament but the Old Testament, the Koran, and other holy books?

«That goes without saying,» Cardinal Bea answered.

Early the next morning I left Rome, changing planes in Zurich and arriving in Moscow shortly after noon.

One thing that concerned me was the matter of an interpreter. Over the years, in various parts of the world, I had accumulated many examples of mistakes or distortions in meaning caused by faulty translation. Even the best interpreters sometimes had difficulty in conveying the proper nuances. At the Dartmouth conferences, I had been impressed with the ability of the Russian interpreters. Oleg Bykov, in particular, seemed to me to have a flair for the American idiom. I wondered if it would be possible to have Bykov with me at the meeting with Mr. Khrushchev. I decided to speak to Alexander Korneitchuk about it. Mr. Korneitchuk had been chairman of the Soviet delegation to the Dartmouth conference and was a personal friend of Khrushchev’s; both came from the Ukraine. When I asked about Korneitchuk, I learned he was in the hospital but that I would be permitted to see him.

Korneitchuk’s private hospital room was bright, commodious, well-furnished. Korneitchuk was waiting at the door of his room, looking dapper in an elegant bathrobe. He joked about his health, saying that his incarceration in the hospital was a plot by rival playwrights to keep him out of competition. He had foiled them by writing two plays while on his back. He had some chest pains, he said, but he was not uncomfortable. He had been promised a complete cure; he had a little vodka in his closet to prove it. He poured drinks, then asked the nurse to bring us fruit, tea, and cake.

He confirmed everything I had heard about Khrushchev’s need to produce effective agreements with the United States in the wake of the Cuban episode. Khrushchev’s supporters felt that the decision to withdraw from Cuba was an act of statesmanship and high responsibility, and might represent a vital turning point in the Cold War. Others, however, reserved judgment, saying it would be necessary to come up with specific agreements before such an optimistic interpretation could be sustained.

What would happen, I asked him, if Khrushchev failed to obtain the agreements he needed to justify his decision to remove the missile bases from Cuba?

It was important to understand, Korneitchuk said, that Khrushchev was irretrievably committed to two objectives. One was to upgrade the living conditions and spirits of the Russian people. The second was to eliminate the dangerous feelings of suspicion and hostility toward the West implanted under Stalin. Specifically, this meant ending the arms race.

The two objectives were related, Korneitchuk said, because only by lifting the burden of arms manufacture would it be possible for the Soviet economy to be freed for economic development and improved living conditions. Co-existence, therefore, was not just a matter of foreign policy; it was directed to the most important need of the domestic economy itself.

Khrushchev would not easily be deflected from these commitments, he said. Even if he didn’t get the agreements he thought would be acceptable to the United States, he would persist with his policy of co-existence as long as he had enough support inside the country.

I didn’t want to tire my host, but there was one small point I thought I might bring up. I would consider it a great favor, T said, if I could bring my own interpreter to the meeting with Mr. Khrushchev. Not that I lacked confidence in the person Mr. Khrushchev might designate. It was just that I thought it might be more satisfactory if I could talk to the Chairman through an interpreter who was accustomed to my Americanese. (Russian interpreters tend to be divided into two groups: those whose English was learned in England or under British-taught instructors, and those who speak colloquial «American.» Bykov belonged to the latter group.)

Korneitchuk said he would see what could be done and would inform me at the hotel.

The next morning Oleg Bykov telephoned to say that he had been designated as my interpreter for the meeting with Khrushchev. He also said that the Supreme Soviet— equivalent of Parliament or Congress—would be in session that day. Premier Khrushchev would be addressing the delegates at 2 p.m. This would be Khrushchev’s first public accounting for his decision to withdraw from Cuba. He probably would reply to the criticisms of the Chinese Communists. Chairman Khrushchev thought I might be interested in going. Would I accept his invitation?

Naturally.

That afternoon Oleg escorted me to one of the largest buildings in the Kremlin complex. We ascended a long, red, deep-carpeted stairway to a large foyer adjoining a rectangular, simply designed auditorium where the representatives from the various districts were taking their seats for the afternoon session. Oleg took me directly to the Kazakhstan section toward the front of the hall.

Shortly after we were seated, two women walked up the aisle and took their places three rows in front of us. Oleg identified them as Mrs. Khrushchev and the wife of Marshal Tito. A minute later Nikita Khrushchev came to the platform. An ovation ensued. After returning the applause Russian-style, Mr. Khrushchev began to talk over the clamor and the hall soon became quiet, filled only by the Chairman’s staccato delivery. The first part of his talk dealt with economic conditions inside the Soviet Union. Then he entered into a review of foreign affairs and proceeded to the matter of Cuba.

He said the decision to equip Cuba with modern weapons was dictated by American plans for invading Cuba. Then, as the crisis developed, he said, it became clear that the Cuban situation was getting out of hand and that a terrible culmination was building up. Both he and President Kennedy had the joint responsibility to prevent the Cuban crisis from leading to nuclear war. He said the President had assured him that the United States had no intention of invading Cuba. Therefore he felt it was right to remove the missiles. But the Chinese were attempting to make it appear that a sober, responsible decision to avert nuclear war was a repudiation of Marxist-Leninist ideology. One could only be astounded, he said, by such tortured logic. It was like being in a fight and having someone on the side lines goad you on to your own destruction. He didn’t regard the responsibility given to him by the Party as a license to help destroy the human race. Marx and Lenin, he said, were no freebooters or military adventurers. It would not be possible to pursue the triumph of socialism on the radioactive ruins of civilization. As for the derisive comment of the Chinese that the United States was bluffing and was only a «paper tiger,» he commented that the tiger had nuclear teeth. He insisted that the Soviet Union would not let the Cuban people down and intended to stand by its commitment. Meanwhile, he said, he would do everything he could do to seek a peaceful resolution of the Cuban situation and all the other critical situations around the world. The remainder of Chairman Khrushchev’s address was devoted largely to ideological matters.

On the way back to the hotel, I asked Oleg what he thought of the talk.

«Well, you were able to see for yourself,» he said. «The old man really means it. And the people know he means it. I think the Chinese know he means it, too.»

For five hours that evening, I rehearsed with Oleg for our meeting the next morning with the Chairman. I wanted to be sure not only that everything I would say to Khrushchev was completely intelligible to Oleg for interpreting purposes but also that the emphasis would be accurate. I encouraged Oleg to ask questions about shadings in meaning—something that would have been awkward during the session with the Chairman. It developed there were at least three dozen terms whose precise equivalents were lacking in the Russian language, and it became necessary to develop context to convey meaning. Exhausted but hopeful, we ended our session at 1 a.m., after agreeing to meet at breakfast for a final go-round.

The next morning we tried to anticipate some of the questions Mr. Khrushchev might ask. At 10:15 a.m. we left the hotel for our 11 a.m. appointment at the Kremlin.

Nikita Khrushchev had his offices in a building of pre-Revolutionary vintage on a Kremlin side street not open to the general public. The main doorway was so unpretentious that I thought for a moment we were using the back entrance. The small foyer was more suggestive of a lobby in a modest apartment house than the reception hall of the headquarters of a major government.

Bykov and I were ushered into a small anteroom. We were hardly seated when Mr. Khrushchev came to the door, greeted us, and escorted us to his adjoining office, the most conspicuous feature of which was a long, narrow conference table that could accommodate twenty persons or more. The table was pressed against Mr. Khrushchev’s desk and made a T design.

I introduced Oleg Bykov.

«So this is the famous interpreter you bring with you,» Mr. Khrushchev said. «Tell me, Mr. Bykov, have you ever sat in the Prime Minister’s chair before?»

Oleg mumbled what I took to be the equivalent of “No, sir.»

«Very well,» said the Chairman. «You’ll now see how it feels. I will sit opposite Mr. Cousins at the conference table and you will be at the Prime Minister’s desk in the center. If the chair’s too uncomfortable, I will requisition a better one.»

Oleg assured him he would be most comfortable. We took our places.

«Now,» said the Chairman, addressing me, «we will have a man-to-man talk. Please tell me about your family. In Russia we like to hear about families before we talk about business.»

I spoke about my wife and four daughters. The Chairman asked me if I had brought them with me. When I said I had not, he looked at me severely and said, «For shame.»

I explained that the girls were at school, but he dismissed what I said with a wave of the hand.

«School? Nonsense! They don’t teach anything in the schools as important as they could learn traveling with Papa. Weren’t they even curious about your trip?»

I said that the youngest, then twelve, had asked me before leaving whether I was terrified about being alone with the mighty head of all the Communists. Then, without even waiting for my answer, she said, «Daddy, when you see him, just imagine he’s an old uncle and you won’t be scared anymore.»

«My grandson gives me good advice, too,» Mr. Khrushchev said. «In fact, sometimes I make decisions that members of the Party say they don’t fully understand. When they ask me how I happened to decide, I tell them this is what my grandson told me to do. They think I’m joking. They don’t know how wise my grandson is.»

I noted that Mr. Khrushchev had had a busy time with the Supreme Soviet and thanked him for the opportunity to sit in on the session at which he spoke. Was he exhausted?

It’s really not too bad, but I am a little tired now that it’s over,» he said.

Then he asked if I had heard Tito.

I said no. Tito had spoken at the morning session.

«The Tito matter gave me a few more gray hairs,» he said. «As you know, our relations with Yugoslavia are rather delicate. I don’t want Marshal Tito to think that we are too big to have equality with him in our relations. We have our differences, and I’ve tried very hard to persuade him that I respect his position on these differences and that we’re not trying to gloss over them.

«So yesterday, in introducing Marshal Tito to the Supreme Soviet, I made it clear that, even though our two countries disagreed on certain matters, we were not allowing these differences to stand in the way of our friendship.

«Marshal Tito acknowledged the introduction very cordially and spoke along the same lines as I did. He received a very warm response at the end of his talk. Then there was a recess for a few minutes. It had become pretty stuffy and I needed air. I went out for a walk.

«One thing I like to do while I walk is listen to music.

I have a small transistor radio I keep in my pocket. And so yesterday, as I took my walk, I held the tiny radio to my ear, listened to the music, and tried to clear my mind. The music was interrupted for a news bulletin. The announcer reported the morning session of the Supreme Soviet just completed. He said Marshal Tito and I had spoken and we had announced that all differences between our two countries had been fully resolved. I could hardly believe my ears. We had done nothing of the sort. What really troubled me, of course, was that if this news report came to the attention of Tito, he would think I was playing a double game—saying in his presence that I recognized the fact of the important differences between tis but telling a different story to the press, glossing over our differences and making it appear they no longer existed. How could that idiot of an announcer have said such a stupid thing? What happened, of course, is that some journalists just don’t know how to handle good news.

«Now, what should I have done? Should I have rushed back to Tito and apologized? It was possible he knew nothing about it. Why confuse him? In fact, he might be even more upset by the apology than by the news bulletin. But if I did nothing, wouldn’t I be taking a chance that somebody in his entourage might have heard the broadcast and elaborated on it in retelling, with the result that all our efforts to establish good relations with Tito would be jeopardized? Besides, wouldn’t he assume that the news story was official if I didn’t repudiate it?

«Finally, I decided to wait twenty-four hours. I figured that if he or his aides had heard the broadcast, he would be certain to protest. In that case, I could say, ‘Yes, I know it’s a stupid, dreadful thing. Please pay no attention to it. I’m investigating to find out how it happened and I intend to give you a report.’ But if, at the end of twenty-four hours, he says nothing to me, the chances are he knows nothing about it and there’s no problem. So, I’ve still got an hour to go. The things a man gets into when he gets into politics…

He shook his head. «But you didn’t come here to hear me complain about my problems, especially after having lessened to me for two hours yesterday. That’s a long time for a capitalist like you ю listen to an old Communist like fine. I hope I didn’t shake you in any of your beliefs.»

I said I had listened with the keenest interest to everything he had said and was glad to reassure him he had not deprived me of my philosophical underpinnings. I added that I was pleased to hear him tell the Supreme Soviet that there had been an economic upturn.

The Chairman said his country had been making progress. In industry, they had surpassed their quotas. That didn’t satisfy him. The quotas should have been set much higher. But at least the increase in industrial production gave promise of much larger gains ahead. In agriculture, they hadn’t done nearly so well. They were ahead of the previous year, but still far behind where he thought they ought to be. One thing they had done might help, he said. They had just divided the Communist Party into two major sections—one industrial, one agricultural. In this way he thought they ought to be able to sharpen the lines of responsibility.

But they were still plagued by bureaucracy, he continued. The bureaucracy made for inefficiency. If something went wrong, it was always someone else who was responsible. The bureaucracy and the incompetence didn’t happen overnight; they couldn’t be eliminated overnight. They were built into the way things were done during the long years under Stalin. The Chairman said people had a habit of finding easy excuses for doing the wrong things. He would be told this was the way matters had always been and that it was the only way people knew how to do them. He realized, therefore, that there would have to be something approaching a psychological upheaval before people would be ready to face up to the need to change the way they were doing things.

This meant de-Stalinization. The bureaucracy had grown up under Stalin. Only by changing the attitudes toward Stalin could they change everything else that had to be changed, he said. But this was a real problem. Stalin had been worshiped by the Soviet people. Millions of people had gone off to war and died with the name Stalin on their lips. They had no idea how irresponsible and irrational he was. Did anyone have the right to disillusion those who had survived the war? Wouldn’t there be a profound emotional shock if they were told that the man they had venerated for so long hadn’t really known what he was doing?

«I wrestled with the problem,» he said, «then finally decided I had to tell the people the truth. At least twice I made long statements on the subject, telling the full story. You would suppose that by now people would know. Not so. Every day I meet otherwise intelligent people who still think Stalin was sane.

«There was a very important difference between Lenin and Stalin. Lenin forgave his enemies; Stalin killed his friends.»

All the time he spoke his hands were folded quietly on the table. I had expected him to be volatile and free-swinging in manner, judging by the newsreel pictures showing him engaged in extravagant gesturing and posturing. Yet his private demeanor couldn’t have been more restrained or polite. He spoke in subdued tones. Even his clothes added to the impression of restraint. He wore a dark blue suit, white silk shirt, solid gray tie held in place by a small jeweled stickpin. His shirt had French cuffs with large gold links. The break in the cuffs revealed long-sleeved winter underwear. The correctness and elegance of his attire compared to my own made me feel somewhat awkward. I looked down at my own unmoored tie and my plain cuffs. I tucked the tie inside my jacket.

The Chairman said he was happy to accept the suggestion of several of the Soviet delegates who had been to the Andover conference in the United States that I be invited to come to speak to him. He said he had seen various materials prepared by Father Morlion that had been sent to him in advance of our meeting. Then he said he understood I had just come from Rome.

«What can you tell me about the Pope?» he asked. «Is he very ill? He made a big contribution to world peace during that terrible time of the Cuban crisis.»

I said there was intense concern for his health. Despite his illness, Pope John was determined to use his remaining energies in the cause of peace. I emphasized, of course, that I was speaking not as the official emissary of the Pope or of the Vatican in general. I had coms in a private capacity, but I had seen Vatican officials and Avas in a position to convey my impressions.

«I understand completely,» the Chairman said. «No one need be committed. About the Pope: He must be a most unusual man. I am not religious but I can tell you I have a great liking for Pope John. I think we could really under-stanff each other. We both come from peasant families; we both have lived close to the land; we both enjoy a good laugh. There’s something very moving to me about a man like him struggling despite his illness to accomplish such an important goal before he dies. His goal, as you say, is peace. It is the most important goal in the world. If we don’t have peace and the nuclear bombs start to fall, what difference will it make whether we are Communists or Catholics or capitalists or Chinese or Russians or Americans? Who could tell us apart? Who will be left to tell us apart?»

His eyes took on a pensive look.

«During that week of the Cuban crisis the Pope’s appeal was a real ray of light. I was grateful for it. Believe me, that was a dangerous time. I hope no one will have to live through it again Well, I think you know how 1 feel about it. You heard me speak about it yesterday.»

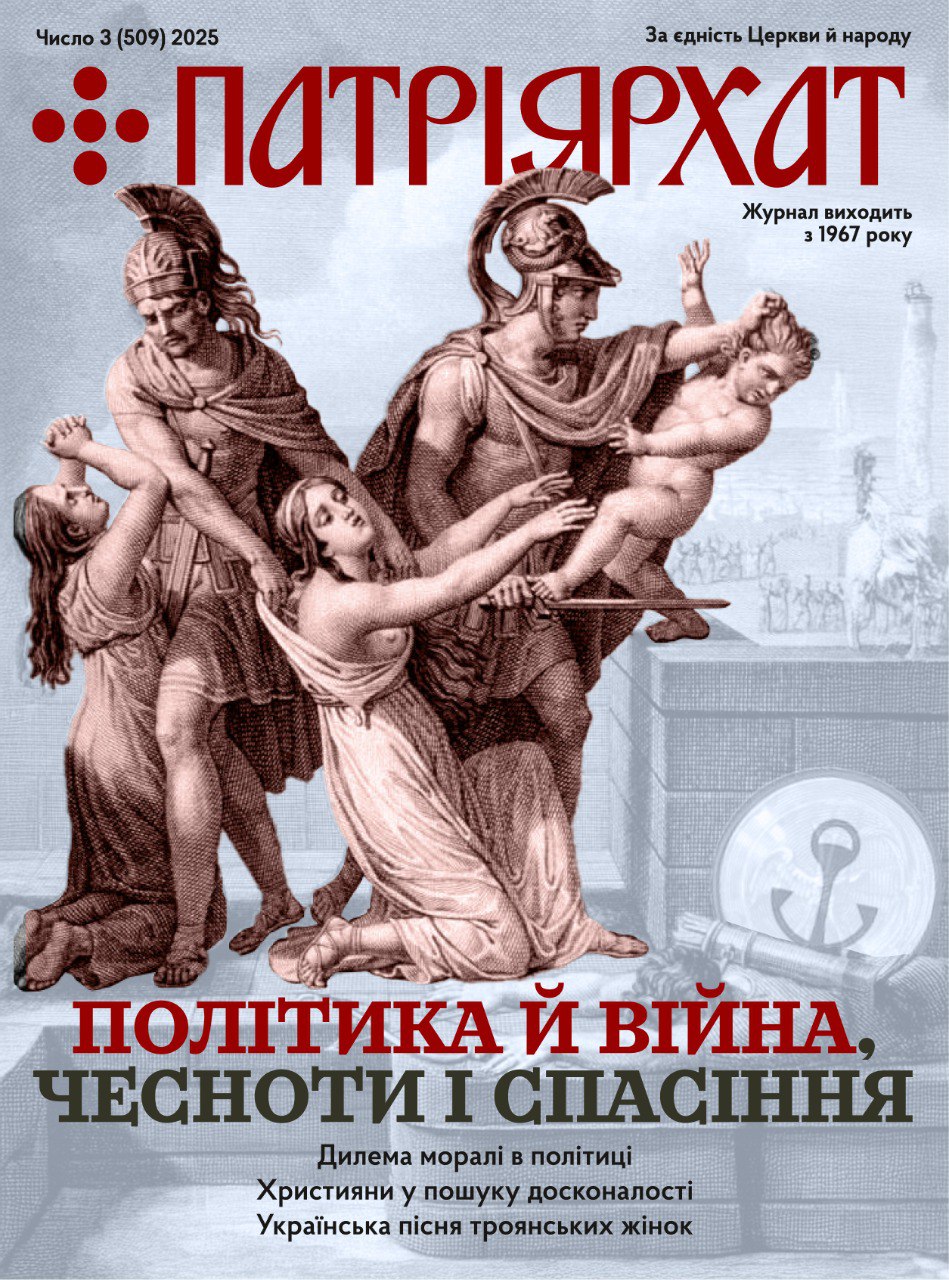

(To be continued next issue)