National Catholic Reporter November 30, 1984

By PATRICIA SCHARBER LEFEVERE

Special Report Writer Kansas City, Mo.

THE LAST WILL and testament of the recently deceased Ukrainian Catholic rite Patriarch Josyf Slipyj indicates that a secret Vatican document was known to him that, if enacted, would spell a death blow to the Ukrainian church.

In his will, written in Rome before his death Sept. 7, Slipyj said, “Today we have a secret document concerning contacts between the Roman Catholic see and the patriarch of Moscow,” which “are, if you will, a death sentence for our Ukrainian church.” Not only did this secret document threaten the future of the Ukrainian church, but it could also harm the universal Christian church, the cardinal wrote.

In his 30-page legacy, addressed to the six million Ukrainian Catholics worldwide — 300,000 of whom live in North America — Slipyj enjoined Ukrainian Catholics to live as children of the light, taking no part in vain deeds done in darkness, but rather condemning them.

What secret documents the cardinal is referring to may never be clarified. However, only 10 days after his death, a letter from the secretary of the Congregation for Eastern Churches (C£C) indicated that the Vatican found “shortcomings and abuses” in the Ukrainian eparchy (see letter, this page). These include the ordination of married clergy, the issue of the Ukrainian patriarchate and “the lack of discipline and spiritual life” among Ukrainian clergy.

Both Newsweek and the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette reported the “secret suspension letter” in early November issues, causing an uproar among many in the Ukrainian church. NCR received a translation of the letter, written in Italian, from sources close to Ukrainian bishops in North America. Several of the bishops met Nov. 19 and 20 in Philadelphia, where the matter was discussed.

Reliable sources confirmed that the letter had been sent to Bishop Isidore Borecky of the Toronto diocese, to his auxiliary and to a bishop in Australia. It may have gone to other bishops, though probably not to all of them as indicated by Newsweek. In 1970 Borecky ordained a married man, but after receiving several reprimands from Rome, he did not do it again. Toronto has three other married priests — each of whom is thought to be affected by the CEC letter.

Borecky told the Post-Gazette he knew nothing about the letter, calling it “unbelievable” and “a great injustice to the Holy Father.” In a joint letter to Newsweek’s editors, four U.S. bishops of the Ukrainian rite categorically denied “that we have received instructions to ‘suspend them all.”

Moreover, Archbishop Maxim Hermaniuk of Winnipeg, Ukrainian metropolitan for Canada, also said no Canadian prelate had received any secret letter as described by the reports. If such a document existed, he said, it was probably sent to one bishop and pertained only to a special case or cases in his see.

A source who had met with some of the bishops attending the Philadelphia meeting said the bishops felt “bound by a promise of secrecy” not to say they had received such a letter or what it contained.

Journalist Bohdan Hodiak of the Post-Gazette tried to find out the number of priests suspended (Newsweek had reported 20 ordained since 1963) by telephoning Archbishop Myroslaw Marusyn, secretary of the CEC, in Rome recently. Marusyn and Cardinal Wladislaw Rubin signed the controversial statement. Reliable sources said Rubin, a Pole, had given his signature from his hospital bed in Rome.

When asked whether he personally had written the letter referred to in Newsweek, Marusyn replied: “No one has a right to publish letters sent from the Vatican.” Married men who were ordained priests are considered in a state of automatic suspension, the archbishop said, and their cases would be reviewed individually.

“We are trying to help them. We only want the good,” Marusyn told Hodiak. “If you were here in Rome, I could tell you more. But I cannot on the telephone,” Marusyn said and hung up.

Slipyj is reported to have ordained about 20 married men since 1963 as priests of the Western Ukraine, though they never served there. Instead, many were sent as foreign missionaries to serve Ukrainians in North America. In this way, Slipyj got around the ban on married priests in the West.

Slipyj spent 1955-1963 in Stalinist prison and labor camps for refusing to give up his alegiance to the pope. Aged 93, and reportedly in sound mind at the time of his death, Slipyj was one of only a few Ukrainian clergy to survive the Russian labor camps during World War ІІ. Following the war, he was offered the post of metropolitan of Kiev or even patriarch of Moscow if he would convert to Orthodoxy, which he refused, according to Father Myron Tataryn of St. Catherine’s, Ontario.

Tataryn, who translated Slipyj’s will into English, said he thinks the late cardinal never saw the CEC letter. “He would have squashed it; he had enough health at the end to do that,” Tataryn said.

Tataryn, press spokesperson for an internaonal forum on Patriarch Andrei Sheptyts’kyi, scheduled for Nov. 22-24 in Toronto, said he expected the conference would include lively discussions of the suspension issue. “The swiftness of the bishops’ denial reinforces my suspicion that something’s definitely been done,” he said.

The priest further noted that, within days of Slipyj’s death, his successor, Major Archbishop Myroslav Lubachivsky, circulated a pastoral letter outlining his vision for the Ukrainian church. Ukrainian bishops and the CEC rejected the letter, Tataryn said.

Lubachivsky, who is not to be referred to as patriarch — Marusyn told the Post-Gazette — was not Slipyj’s choice. Although some Ukrainian bishops have criticized his appointment, NCR learned, his was the top name among three submitted to the Vatican after the 1980 Ukrainian synod in Rome.

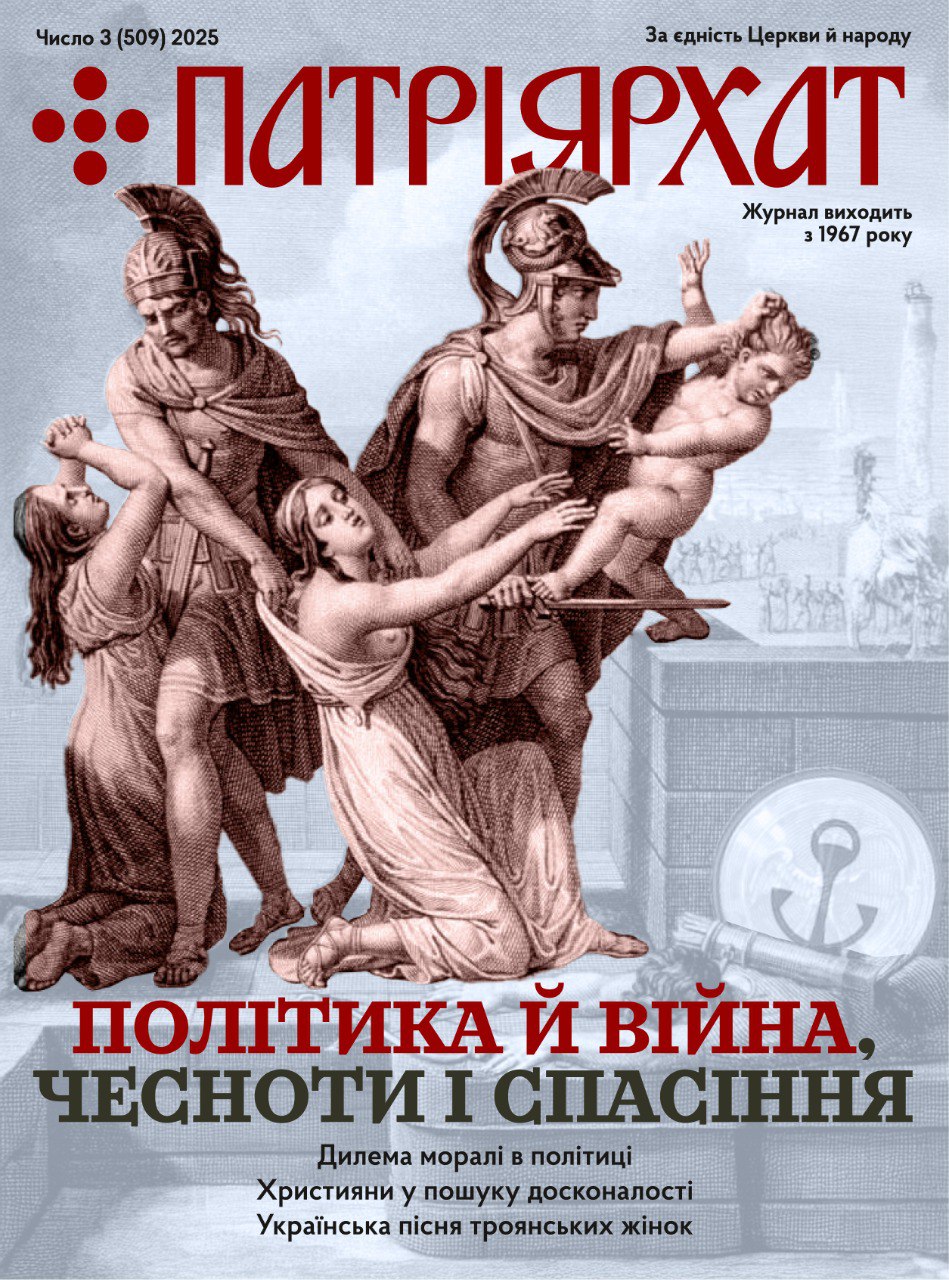

The patriarchy issue is not new. Ukrainian Catholics have long petitioned Rome to create a patriarchate, such as the Armenians and Melchites have.

Critics of the patriarchal movement say the title would be only symbolic. There is also the problem of a patriarchal seat. Because Moscow will not allow a patriarch to reside in the Ukraine, he would be a patriarch in exile. The patriarchy is an issue many Ukrainian rite Catholics think Rome will never support.

Rome “wants dialogue with the Soviets and closer relations with the Russian Orthodox church. We are a stumbling block said a yo.ung married priest in the Midwest who did not want his name used. He called Lubachivsky’s appointment an act of “sabotage” of the Ukrainian church. Contrasting the two leaders, the priest characterized Slipyj as feisty and Lubachivsky as quiet, scholarly and ready to do exactly what Rome wants.

This had been the model of Ukrainian patriarchs from the mid-19th century to the time of Sheptyts’kyi, who, in Tataryn’s words, put a halt to “the degree of Latinization and ‘yesmanship’ so rampant” in the Ukrainian church. If he were alive now, Sheptyts’kyi, considered one of the fathers of ecumenism, might well be disappointed to discover that ordinations of married clergy — common to the Ukrainian rite for centuries — may no longer be valid.

As Tataryn put it, “The real issue here is not just one of married priests, but it’s whether we can continue to be ourselves: Orthodox in tradition and yet united with Rome. If we cannot, then the ecumenical dialogue between Rome and the Orthodox is a shame.”

Meanwhile, other Ukrainian sources in Canada who spoke with NCR, noted the irony of the increasing number of Episcopal priests in the U.S. being ordained for Catholic parishes.