When, at the beginning of the 20th century, Ukrainian national and political life began to revive, church architecture, which, according to researcher Stefan Tarasenko, was the highest creative achievement of the people, was dominated by the pseudo-Russian style imposed by the autocracy. “An oppressive dead silence, no movement, the stench of desolation and the putrid decay of corpses,” wrote Vadym Shcherbakivsky in his work *Architecture Among Different Peoples* (1909), describing the time when, from the beginning of the 19th century, the tradition of building in the national style was interrupted on Ukrainian lands under the Russian Empire. In the year this book was published, the prominent historian, considered the father of Ukrainian anthropology and ethnography, Fedir Vovk, traveled through Volyn. The century-long attempts to Russify Volyn led him to this conclusion: “My attention was drawn only to ancient church structures, as the new ones are hardly capable of interesting not only an ethnographer but anyone, due to their gray, formulaic official architecture.”

The Revival of Ukrainian Church Architecture in the Territories of the Russian Empire

At the time when Fedir Vovk and Vadym Shcherbakivsky criticized synodal architecture, a return to Ukrainian forms in architecture had already begun, but it manifested most prominently not in church architecture but in civil construction, as the Church remained an instrument of incorporation and control policies, aimed at Russifying the population and territories. From 1721, the Russian Church was governed not by a patriarch but by a synod under the supervision of a minister who was a tsarist official. Dioceses corresponded to the boundaries of gubernias, and priests received salaries from the state treasury. All higher church positions in Ukraine were held by Russians. The Church was so Russified that in 1919, there was not a single active Orthodox Ukrainian bishop. Architectural projects were approved from above—by the tsar, the synod, or diocesan authorities. There was no room left for folk traditions or national architecture. In some cases, figures of the Russian Orthodox Church of Ukrainian origin preserved their identity and at least once attempted to express it in architecture.

Exceptional examples of the return of Ukrainian elements to church architecture (not counting objects with individual Ukrainian-style details) from the first third of the 19th century to the First World War in territories controlled by the Russian Empire are two churches: one in Pliashivka in Volyn and another in Plishyvets in Poltava region. In Pliashivka, between 1910 and 1914, the memorial Yuriivska Church in the Ukrainian Baroque style was built by architect Volodymyr Maksymov under the supervision of Oleksiy Shchusev. In Plishyvets, thanks to the collaboration of a native of the village, Ukrainian religious figure Bishop Parfeniy Levytsky, historian Dmytro Yavornytsky, and Russian architect Ivan Kuznetsov, a grandiose nine-part stone church was constructed. It was inspired by the Cossack cathedral in Samara (formerly Novoselytsia, Dnipro region), consecrated in 1778. On this occasion, Shcherbakivsky wrote that Ukrainian architecture “is transitioning from wood to stone and developing.”

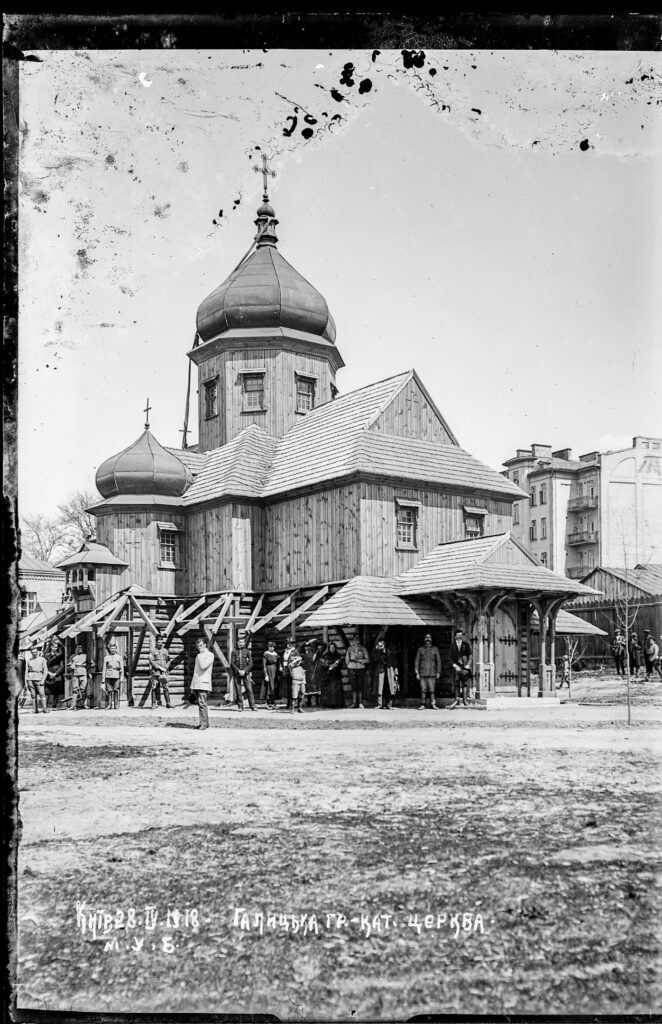

During the liberation struggles in Kyiv, a Greek Catholic wooden church of the Sacred Heart of Christ was built in Ukrainian forms. Its construction was linked to the presence of Ukrainian Sich Riflemen in Kyiv, initiated by Andriy Sheptytsky. The structure was completed in the spring of 1918 on the site of present-day Volodymyr Vynnychenko Street, 10–12. Between 1917 and the 1920s, this shrine was known as the church of the Sich Riflemen of the Galician-Bukovinian Battalion. It was a three-part, single-domed church covered with shingles, with a pentagonal altar in plan. Above the central section rose an octagonal drum with a pear-shaped dome. Based on photographs, the church had small side arms or wings on either side of the central structure. One of the arms had a pear-shaped finial, similar to the central dome. This church bears some resemblance to the projects of architect Vasyl Nahirny, who designed hundreds of stone and wooden churches, including single-domed wooden churches, cruciform in plan with a faceted altar, rectangular side arms, and a narthex. The building shows some stylization reminiscent of the St. George Church in Drohobych. The Kyiv church of the Sacred Heart of Christ was destroyed by the communists in 1935.

Elements of Ukrainian church architecture were fully expressed in civil construction. This is evidenced, for instance, by the elegant tower on the Boyko House in Kharkiv (1911–1913), built by Serhiy Tymoshenko. The same group includes the house of millionaire Khrennikov (a friend of Yavornytsky) in Dnipro, constructed by architect Petro Fetisov. This house had a facade with three domes in the style of Left-Bank Baroque churches.

At the same time, the Russian Orthodox Church continued to produce formulaic “synodal” churches throughout Ukraine until 1917. In Pochaiv, where the grandiose Trinity Cathedral was built in 1910–1912 according to Oleksiy Shchusev’s design, Russians lacked “a shrine in the style of the Orthodox Russian land.” Furthermore, by the time of the collapse of the Russian Empire, reconstructions in the Russian style had already affected many church buildings constructed before the mid-19th century: from minimal interventions such as the demolition of encircling galleries and covering with oil paints or replacing iconostases, to the addition of bell towers to the narthex, changes in dome shapes, or even the complete demolition of an old church due to “dilapidation” and the construction of a new one. These were built in Russian forms, with old icons or iconostases transferred from the previous church. The scale of church construction and interference with old churches is indicated by figures: in western Ukraine and Belarus — lands taken by Russia from the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth — the number of Orthodox parishes and churches grew from a few hundred in 1772 to 6,000 parishes, with 9,000 churches and chapels, by 1914. Some churches were built “for growth.” Władysław Reymont wrote in 1910 that in Chełm, the number of churches was impressive, all beautifully equipped and large, but they stood empty, “because there are not enough Orthodox believers to fill even one.”

In 1912, one of the deputies to the Russian Duma from Poland, Stefan Godlewski, summarized: “The task of the Russian state is to Russify everything non-Russian and Orthodoxize everything non-Orthodox.”

Thus, when we now see pseudo-Russian bell towers or domes with kokoshniks added to the narthex or above the central section of wooden or stone churches, exterior walls painted blue, tin roofs, and onion-shaped finials replacing traditional Ukrainian tops; when we see the removal of encircling galleries around wooden churches, altered window shapes, and pediments, these are all consequences of the Russification policy, which have nothing in common with Ukrainian church architecture!

Moreover, the influence of Russian synodal architecture in Ukraine remains so significant that modern Ukrainian church construction still reproduces Russian planning: a high bell tower attached to the central structure, dominating the spatial composition, with churches mostly single-domed. The situation was somewhat better in central Ukraine, where Baroque traditions were very strong. Although the Moscow Patriarchate used these churches, their forms remained Ukrainian. However, recently, the Moscow Patriarchate has increasingly become an instrument for imposing Russian forms in architecture, as it was during the empire. For example, consider the replication of Kizhi architecture in Karelia at the skete of the Sviatohirsk Lavra or the creation of pseudo-Russian churches with exaggerated onion-shaped domes in Kyiv on Brest-Lytovsk Highway and near the Olympic Stadium, which are stylizations of the tented church style typical of Russian architecture and contrary to the Ukrainian tradition of vertical spatial revelation in interiors and upward aspiration.

Initially, Ukrainian Architecture Influenced Russian Architecture

Interestingly, long before the Russian architectural dictate in the territories of the Russian Empire, another architectural “expansionism” was taking place — Ukrainian. After 1654, Ukrainians, particularly graduates of the Kyiv-Mohyla Academy, began to occupy prominent positions in the church and state hierarchy of the empire.

For example, the ruins of the Church of the Exaltation of the Cross from 1737 in the village of Ukhtoma (now Volgograd Region) remain — a three-part, single-domed church executed in typically Ukrainian forms. A vivid example of Ukrainian style is the architecture of the Trinity Monastery in Tyumen. A graduate of the Kyiv-Mohyla Academy, Filofei Leshchynsky, built a cruciform, five-domed Church of Peter and Paul (1726), a three-part, three-domed Trinity Cathedral (1717), and a two-story refectory Church of the Forty Martyrs (1715).

In Tobolsk, Metropolitan Antoniy (Stakhovsky), also a graduate of the Kyiv Theological Academy, invited Ukrainian master Korniliy Mykhailov from Perevoloka to build the Church of the Epiphany (1737). Thus, Ukrainian architecture spread far beyond the areas of compact Ukrainian settlement. Ukrainian influence left not only architectural monuments but also brought changes to Russian church construction, contributing to phenomena such as “Siberian Baroque.”

Another example: the Pskov Diocese was led exclusively by Ukrainians and graduates of the Kyiv-Mohyla Academy throughout the first half of the 18th century. Ukrainian features are noticeable in the architecture of the Pskov-Pechersk Monastery, particularly in the Dormition-Pokrovsky Church, where influences from the churches of the Kyiv-Pechersk Lavra can be traced.

A remarkable example is the preserved church in the village of Plissa near Nevel in Pskov Region, built in 1747. This is a wooden cruciform church in the style of Baroque churches of Podillia or Left-Bank Ukraine, with a wonderfully preserved Ukrainian-style iconostasis, likely created by visiting craftsmen from Ukraine. At the time of its construction, Plissa was part of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, and the church may have belonged to the Uniate Church.

It is a well-known fact that Ukrainian architecture was widespread in southern modern Belarus and from Starodubshchyna to Kuban. Don Cossacks emulated the forms of the Baroque church in Starocherkassk: a church built in Dubivka (now Volgograd Region) in 1796 follows the style of the church from 1706–1719. Similar monuments existed in the so-called Yellow Wedge—areas of compact Ukrainian settlement in the Lower Volga. Ukrainian influence was also evident in civil construction, such as Mazepa’s chambers in the Rylsk District of Kursk Region.

English historian-Slavist David Saunders, who defended his doctoral dissertation at Oxford on the topic of Ukrainian influence on Russian culture, noted that Ukrainians always differed from Russians. Although in the late 18th to early 19th centuries, educated Ukrainians benefited from integration into the broader imperial community, the histories of the two peoples were closely intertwined. Ukrainians supplied Russia with state officials, introduced Russians to the world of Slavic culture, and generally had a higher level of education. However, in the 19th century, the situation began to change: Russians started establishing universities in Ukraine.

For a long time, Ukrainians played a significant role: they shaped the idea of the empire’s Slavic identity, brought their own culture into the public discourse, and their contribution added breadth and depth to imperial culture. But, as Saunders believes, Slavic culture is one thing, and Slavic culture under strict Russian control is another.

The introduction of Sergei Uvarov’s state ideology of “Autocracy, Orthodoxy, Nationality” from 1833 effectively ended the coexistence of cultures within the empire. Throughout the 19th century, Ukrainians increasingly thought in terms of separateness and the need to create their own Ukraine, rather than coexistence with the empire. “And Russia, which was neither an eastern nor a western power, began to realize that it could not rely on the south either,” Saunders concludes.

Displacement of Folk Ukrainian Construction with Formulaic Models

Ukrainian researchers of church architecture often cite a decree by Paul I from 1800 banning construction in the Ukrainian style, but no such decree existed; the problem lay elsewhere. Wooden architecture almost disappeared across the entire territory of the Russian Empire in the early 19th century. This may be related to Paul I’s decree of December 25, 1800: “…In all dioceses, if a wooden church burns down, do not allow a new wooden one to be built.”

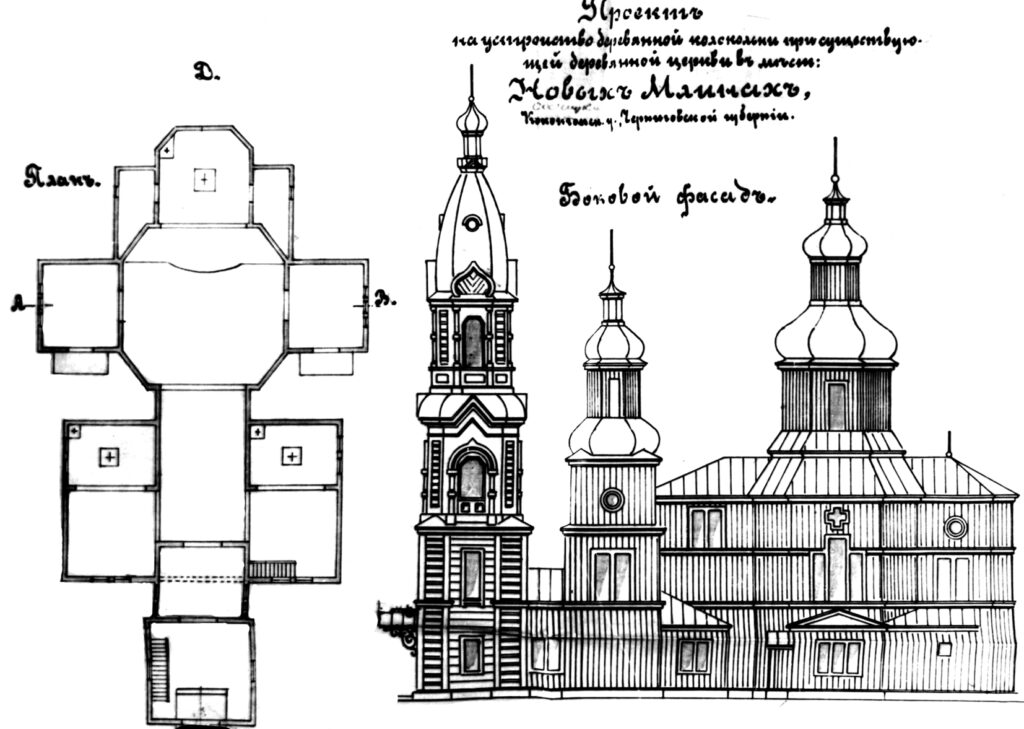

Furthermore, in 1799, after the death of Kyiv Metropolitan Yerofey Malytsky, a non-Ukrainian, Moldovan Gavriil Banulesko-Bodoni, was appointed as his successor for the first time. After him, all Kyiv metropolitans were Russians. “The foreign metropolitan Gavriil considered his main task to ensure that the Church he led would as quickly as possible become fully aligned with the Russian Orthodox Church and indistinguishable from it,” wrote historian Orest Levytsky in an article on the occasion of the church construction in Plishyvets. He notes that in the early 19th century, three-domed churches of the old Ukrainian type disappeared, replaced by churches with new Great Russian forms and decorative motifs. He writes that while Left-Bank Ukraine lived by its customs and Right-Bank Ukraine was under Poland, communities only sought a blessing from the bishop and then independently found a master and agreed on the plan and appearance of the church. However, over time, Russian decrees began to spread to Ukraine, destroying ancient customs. Levytsky states that this led to the disappearance of parish schools and architecture. Under new laws, any community-used buildings required construction permits, including approval of plans, facades, and sections. Only certified architects could perform the necessary work, which folk craftsmen could not do. Consequently, this matter fell under the competence of diocesan authorities, which had architects at their disposal. Levytsky notes that these architects were not very knowledgeable: although they had no instructions on which style to use, they could only produce projects they had studied in their schools. These were “not artists but officials,” who considered parameters like building capacity, with no desire to work on each wooden church, leading to the implementation of formulaic projects. “Church architecture, which once so passionately inspired old Ukrainian masters, like the famous builder of the Novomoskovsk Cathedral, has long been reduced in our land to the level of a craft performed with bureaucratic indifference,” wrote Levytsky, adding that such projects were equally suitable for both Vyatka and Poltava gubernias: “Task him with designing a church at Bohdan Khmelnytsky’s grave, and he will reproduce the Church of St. Basil for you.” He cites the example of the Kyiv-Pechersk Lavra, where “they demolished a stylish 18th-century refectory church and built a new one in a bizarre style—with a dome of Constantinople’s Hagia Sophia and Suzdal-style onion domes. And who can guarantee that in time they won’t rebuild the largest Lavra church in the likeness of Moscow’s Dormition Cathedral! With our historical ignorance and barbaric disrespect for the past, anything is possible.”

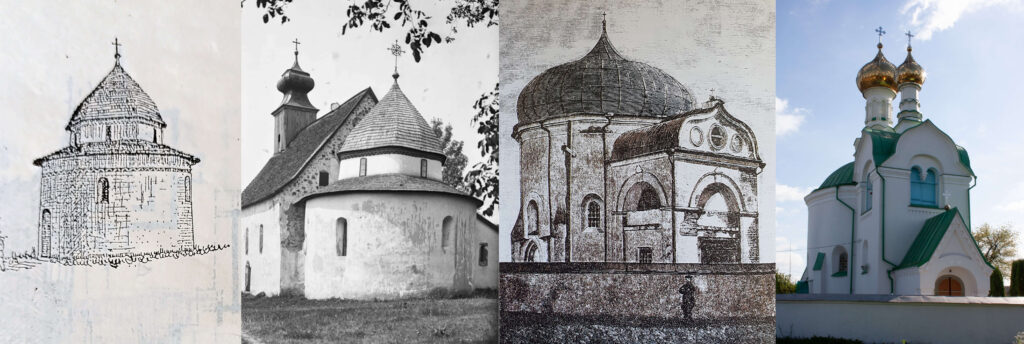

Examples of such policies and ignorance in church construction include the Desiatynna Church, built in 1828–1842 on the foundations of Volodymyr’s Desiatynna Church, with a chaotic mix of styles, and the reconstructions of ancient Ukrainian churches like the Dormition Cathedral of the Zymne Monastery and the Vasylivska Rotunda (12th century) in Volodymyr-Volynskyi.

In fact, the traditions of Ukrainian church architecture continued to be embodied in church architecture in the early 19th century. There was a transitional period. The traditional type of single-domed church remained relevant. For example, in the village of Cherneshchyna in Kharkiv region, architect Petro Yaroslavsky proposed a single-domed church project in 1799. This project survived on paper, allowing researcher Stefan Tarasenko to assert that its composition significantly differed from what was ultimately built, evidently by folk craftsmen.

The folk master who implemented the project preserved the proportions of the central section but altered the width of the altar and narthex according to building traditions. Specifically, he used the proportions of a rectangle where the width equals the apothem of a triangle with a side equal to the rectangle’s length. While the project’s building volume with stylobate and lantern fit into a square, the master violated the principle of cubicity. The height of the central section’s log walls in the interior up to the start of the octagon exceeds the length of the quadrangle’s plan. Instead of a ciborium with columns on the roof, an octagonal light lantern was installed.

In 1801–1804, a pine single-domed church was built in the town of Mena, Chernihiv region, where the central section’s log structure is taller than the side “arms.” Above the first break, the central section’s log walls transition into a proportionally significant octagon, whose width noticeably exceeds its height. It is illuminated by windows placed on the facets oriented to the cardinal directions. The central section is very tall. The altar has a hexagonal plan.

The Pokrovska Church in the settlement of Zemlianky, former Donetsk District, Donetsk Region, built in 1798–1800, had a cruciform plan and a tall main dome with three breaks. A single-domed church in Serhiivka, Udachnenska Village Community, Pokrovsk District, Donetsk Region, built in 1815, had wide “arms” and a later-added bell tower. The destruction of a likely single-domed church with a stone base from the same period was filmed by Dziga Vertov in 1929. The filming of *Symphony of Donbas* took place in Dnipro, Alchevsk, Horlivka, Makiivka, and Lysychansk.

The tradition of three-domed churches continued as well. In the village of Smolianynove, Siverskodonetsk City Community, Luhansk Region, the Church of the Nativity of the Virgin, built in 1803, consisted of three quadrangles, the largest being the nave. The altar and narthex had the same width, but the narthex was longer. A description from 1809 states that the church was made of stone and wood, plastered up to the break, with a roof painted green, domes covered with white tin, and crosses gilded with red gold. According to Tarasenko, this church had a stone base and wooden upper part. He also mentions similar structures in Avdiivka—the St. Michael Church of the 18th century and the two-domed St. Catherine Church in Mariupol from the 1780s.

Among this three-domed type of churches with a stone base, like in Smolianynove, is the Peter and Paul Church in the village of Heorhiivka (now Starohnativka, Volnovakha District, Donetsk Region), built in 1813. It is little studied, with only remnants of the stone base and archival photographs preserved. The church had a massive octagon with fewer breaks. The central dome dominated, while the domes above the altar and narthex were lower. The dome above the narthex served as a bell tower.

Similar projects preserved in archival photographs indicate that there was no sudden disappearance of church construction in Ukrainian traditions under the Russian Empire. It was a gradual process of displacing folk craftsmen with formulaic models provided by diocesan architects. The continuity of Ukrainian traditions in church construction is evidenced by Donetsk region itself!

Even within official church architecture, Ukrainian elements periodically appeared. For example, in the Holy Trinity Cathedral of the Ionynsky Monastery, we see a characteristic dome with a helmet-shaped “Baroque” top. The large wooden Heorhiivska Church in the village of Selyshche, Baryshivka Community, Brovary District, Kyiv Region (1910), is distinguished by Baroque domes, though on a synodal basis. A departure from Russian forms is also noticeable in the church of 1902–1906 in the village of Deptivka, Konotop District, Sumy Region: the vertical revelation of the central section resembles the large Cossack churches of the 18th century.

Intensification of Russification in Architecture

Russification in the architecture of Right-Bank Ukraine became particularly noticeable after the 1830s. Although many Orthodox churches from the first half of the 19th century, built by local nobility for parishioners’ needs, were often executed in the Classical style, particularly in rotunda form, can be noted. Such a church was built in the early 1840s in the village of Svytyaz, Volyn, through the efforts of Count Władysław Branicki’s son Ksawery. The project of this church was based on a traditional three-part scheme, which, under the influence of Classicism, leaned toward a rotunda. Another rotunda church was built in 1839 with neo-Gothic windows in the village of Makiv, Kamianets-Podilskyi District, Khmelnytskyi Region. Its architecture resembled the neo-Gothic palace of Raciborowski nearby. The development of the Northern Black Sea region by tsarist Russia and the growth of southern Ukraine were reflected in the construction of large Classical cathedrals in Odesa, Izmail, Katerynoslav, Mykolaiv, and Kherson. Distinctly Russian elements appeared later.

From the second half of the 19th century, church construction increasingly featured bell towers with tall tented tops, domes with crude onion-shaped false domes or finials, Vladimir-Suzdal brick wall plasticity with kokoshniks, annular arches, weights, and stout columns, and a red-brown color scheme. Sometimes, the reconstruction of old churches seemed absurd. A symbol of thoughtless Russification is the addition of a bell tower in 1888–1890 to the Church of the Nativity of the Virgin (1784) in Rokytnytsia, Kovel region. A church with two towers near the narthex is similar to churches in Mykulychi in Volyn, Novi Mlyny, Berezna in Chernihiv region, and Pereiaslav. The Baroque church in Novi Mlyny was similarly complemented by a later synodal bell tower. The church was destroyed after 1931 but was studied by Tarasenko. Many such examples can be found. The most significant reconstructions affected churches belonging to the Uniate Church in the western territories of the Russian Empire.

Even before the Polotsk Council of 1839, when the Greek Catholic Church was liquidated within the Romanov Empire, except in Chełm, Russian authorities actively erased the Western European appearance of former Uniate churches (even those built before their transition to the Uniate Church). As part of these efforts by the imperial administration, organs were removed, royal gates were installed, illusionistic altars were eliminated, and altar icons reminiscent of Catholic ones were destroyed. In the works of local historian Mykola Teodorovych, known for his historical-statistical description of Volyn settlements, some authentic church elements were labeled “strange,” “Uniate,” or even “icons of Jewish painting.” However, despite deliberate destruction, many ancient relics and traditions were preserved, and Russification did not always proceed unhindered.

A vivid example of Russian interventions in the exterior appearance of architectural ensembles and church interiors is the Pochaiv Lavra, where changes continued from the 1840s to the present day. The interior of the 18th-century Dormition Cathedral remained almost unchanged until the 1840s, as evidenced by Taras Shevchenko’s watercolor from 1846 (left). In 1861, Tsar Alexander II ordered the installation of an iconostasis (right). Works by Luka Dolynsky, created in 1807–1810, were also removed. Later, a tall bell tower was built next to the cathedral, and in 1906–1912, the Trinity Cathedral was constructed.

Teodorovych describes the resistance of Ratne residents: on August 30, 1834, peasants from Vydranytsia near Ratne expelled the priest, removed the curtains from the royal gates, rebuilt the altar, locked the church, and took the keys, loudly cursing the cleric. Similar acts of defiance occurred in other parishes. In the communities of the Resurrection and Illinska churches, parishioners did not allow the royal gates to be closed during the liturgy. One resident even attempted to assault the priest, and only the intervention of Russian captain Sukhotsky prevented the situation from escalating. Analyzing the state of church construction in Volyn in 1887, Pompey Batiushkov reached a conclusion that eloquently confirms the success of the Russification policy: “There is now no place for Ukrainian aspirations to separate this region in any way.”

However, reconstructions took place not only in Russian-controlled Ukraine. In the territories of Maramureș and Ugocha counties (now Transcarpathia), the Uniate Church was established in the first quarter of the 18th century, and church reconstruction began after the visitation of Mukachevo Bishop Manuil Olshavsky in 1751–1752. This reconstruction, according to Roman Mohytych, intensified after the Vienna Council of 1773 and the signing of the so-called Bachynsky-Festevych contract in 1779: the state provided loans for rebuilding old churches and constructing new ones, dictating its architectural requirements. In 1779, three “model” church projects were distributed, and the construction of other types of churches was strictly prohibited. In house-type churches, a framework bell tower, usually false and without bells, became mandatory above the narthex. The towers were topped with a tall spire with four smaller spires at the corners or a Baroque top. In three-domed churches, tented tops were lowered completely or partially and covered with a box vault or topped with steep four-pitched roofs, with a mandatory high framework tower above the narthex.

Churches of the Lemko building school emerged in the second half of the 18th century and developed from the late 18th to the late 19th century. Their appearance was driven by the Uniate clergy’s efforts to align the external appearance of Eastern Rite churches with Roman Catholic ones. The main architectural feature of these churches was the shift of the height dominant from the nave to a tall bell tower integrated above or beside the narthex’s log structure.

A Brief Period of Derussification

Unfortunately, in the 20th century, the revival of Ukrainian church architecture in the Russian Empire was sporadic and more pronounced in Volyn in the 1920s–1930s, when the region became part of Poland. These were the efforts of high-caliber architects whose projects might have been incomprehensible to parishioners accustomed to synodal forms. The most significant efforts toward Ukrainization in architecture were made by Serhiy Tymoshenko, the author of churches in Bronnyky (1928) in Rivne District and Prylutsk (1934) in Lutsk District. The first is a majestic three-domed, three-part church with three breaks, while the second combines Ukrainian Baroque and Functionalism. The same group includes the cruciform Church of the Nativity of the Virgin in the village of Yasynynychi (1937) in Rivne District. Recently, a friend of the author of this article, historian Artur Alioshyn from Lutsk, shared photos of a previously unknown church to art historians in Osmigovychi, Kovel District. The 1939 photographs show a newly built wooden church in the Ukrainian style: a three-part, domeless church, quite common in the region (Mashiv, Zgorany), with a pear-shaped finial in the middle of the gable roof, and the central nave featuring trapezoidal windows characteristic of 18th-century Left-Bank architecture. The photo captures the moment of the consecration of the crosses by the great-grandfather of the author’s daughter. This church has not survived, with only metal crosses remaining. The project could have been designed by Serhiy Tymoshenko or other architects, such as Ukrainian Pylyp Pylypchuk or Tadeusz Krafft, among others.

With Ukraine’s independence in 1991, a wave of church construction and restoration began, reviving sites damaged or repurposed during the Soviet era. Many new churches drew on Ukrainian Baroque traditions, yet Russian colonial legacies persisted. The Moscow Patriarchate’s influence contributed to widespread construction in Russian imperial styles. Rooted in Kyivan Rus, Ukrainian architecture once displayed a rich variety of native forms that were later distorted by Russification and the imposition of synodal templates. This dominance of Russian forms, uncritically accepted by many clergy and church communities, led to their replication in contemporary church design. Pseudo-Russian features such as onion domes and kokoshniks continue to obscure authentic Ukrainian architectural identity. Today, restoring historical monuments requires a conscious choice: preserve colonial alterations or return to the original Ukrainian forms based on solid historical evidence.

Bohdan Voron